Sei Shōnagon (966-circa 1025) was a Japanese author and poet. But she was also a lady of the court in the era of Empress Teishi. That was in the middle of the Heian period.

She completed The Pillow Book in 1002, with the work consisting of observations of her time in court. It’s, essentially, a diary that documents her daily musings over numerous years. So it’s a fascinating look into the Japanese way of life over a 1,000 years ago.

There have been many famous diaries, such as Samuel Pepys’ on the Great Fire of London. But what marks Shōnagon’s work out is its gentle approach and ruminations on everyday life, highlighting that centuries can pass… but us humans don’t change much.

Ancient Diary Entries in the Pillow Book

Shōnagon was a sophisticated woman from a privileged background.

From her protected position in the Japanese Imperial Court. And her book would be a lifestyle column these days, consisting as it does of diary entries, random musings, gossip, poems, aphorisms, and observations.

As these are all from so long ago, there’s the obvious poignancy of these thoughts coming from a human long gone. For over a thousand years Shōnagon has remained silent, but through her work she communicates with new generations who experience a vastly different world to her.

And, after all, one of the aims of any writer is that narcissistic conquest of remaining adored; to live on long into eternity in the minds of future generations adhering to your every word.

It’s true for her. But you can read in Shōnagon’s scribblings a total sincerity.

“I really can’t understand people who get angry when they hear gossip about others. How can you not discuss other people? Apart from your own concerns, what can be more beguiling to talk about and criticise than other people? But, sadly, it seems it’s wrong to discuss others, not to mention the fact that the person who’s talked about can get to hear of it and be outraged.

Of course if it’s someone you have a close bond with, you pause and consider the pain you might cause, and choose to keep your criticism to yourself — though if it weren’t someone close to you you’d no doubt go ahead and say it, and have a laugh at their expense.”

The Heian period was quite a peaceful time and poetry was of the utmost importance. If a potential lover sent you some dodgy prose, this was grounds for dismissing them immediately.

It’s a book you can find in truncated or full form. But it’s one you can dip in and out of – open on any page and find a clever poem, quirky observation, or overly privileged aside.

But The Pillow Book – with its strangely contemporary title – only ever fascinates. If a sense of unparalleled lost time suddenly restored interests you, then it’s a window into the past that you can connect with on a genuine level.

About the Diarist Sei Shōnagon

The Pillow Book was popular in the writer’s era. It actually fits a genre of writing called zuihitsu (随筆). This basically means personal essays of fragmentary ideas from the writer’s surroundings.

The book was forwarded around her court for hundreds of years after her death, only ever in handwritten manuscripts until printing presses of the 17th century arrived.

It’s believed she finished the work whilst in retirement. But there’s no official record, along with few details of her final years.

But asides from editors over the ages adapting and amending sections of her work, these remain her words.

Over 1,000 years after her death and we can find a casual aside on a particular day in history. And that’s the beauty of literature, eh?

A lovely choice of books to review Mr. W. I love the treasured Pillow Book!

LikeLiked by 1 person

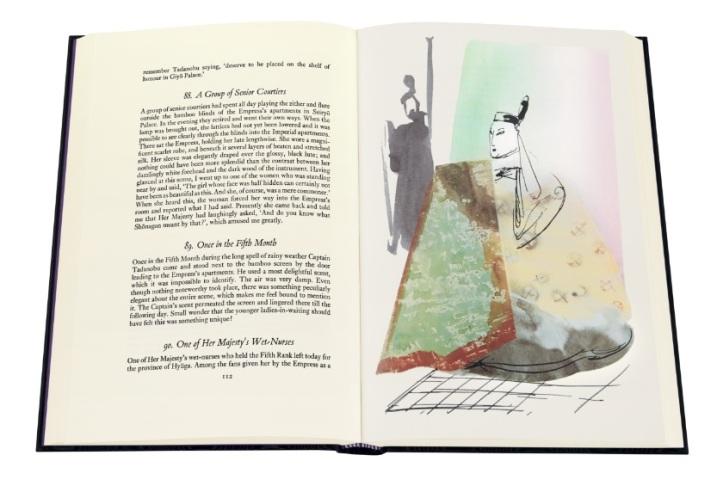

Thank you, madam! It is an excellent one. I want that fancy edition with illustrations, but it’s quite pricey unfortunately.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, it’s really pricey. Sigh, I would love to have it but not now. Thank you again for reminding me of the gem of a book!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You could always steal it. Otherwise, stare at the pretty pictures!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I could go and hang out in Barnes and Noble and buy a latte and just browse through the Pillow Book for a couple of hours. What’s the harm in that?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I went in a Barnes and Noble whilst in ‘Murricah. Excellent place it was, too!

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is fun to hang out there, coffee, tea, scones, brownies, and lo and behold….books!

LikeLike

And the books. That seems to be the main reason to be there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s their original idea, then came the latte and scones. 😊

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wonderful! Good on you for reviewing this book!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanking you. 1,000 years behind on the official release, but better late than never.

LikeLike