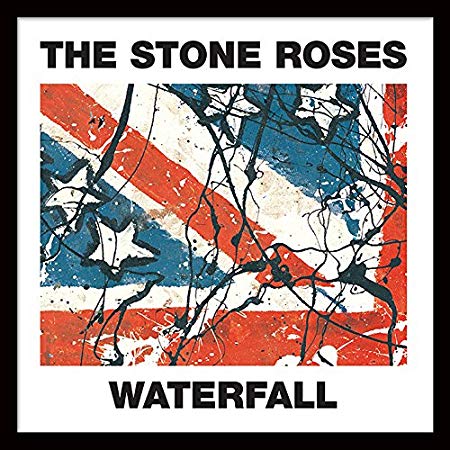

Amongst The Stone Roses’ many classic songs, Waterfall is (for us) the impeccable masterpiece of the lot.

An inspiring and uplifting track, it’s undoubtedly our favourite from the Manchester band. And we’re taking a close look at what makes it a timeless classic, from its progressive structure to those fabulous lyrics.

How The Stone Roses Achieved the Soaring Heights of Waterfall

Now, a quick plug here for John Robb’s highly insightful The Stone Roses and the Resurrection of British Pop. A glorious account of the band’s rise to brilliance.

Thanks to Robb’s relentless detail, we all found out a huge amount about the band’s inner workings during the 1980s.

The shift in music away from the post-punk racket that was the norm. The foundations for brilliance put in place, initially with the arrival of genius drummer Reni in 1984.

By the time of The Stone Roses’ eponymous debut (1989), the band had advanced significantly with their music.

It’s unclear when Waterfall was written. But if you check the band’s live set lists from 1987 to 1988, it’s missing off the former.

So, we’re presuming Brown and Squire had it penned maybe in early 1988.

Waterfall may seem simplistic, but we think that’s deceptively so. It’s multi-layered and there’s a lot going on. John Squire’s looping guitar riff is like a counterpoint-based (contrapuntal) melody building on itself each time around. As if it’s a nod to Pachelbel’s Canon in D.

We debated with someone online years ago. They didn’t like Waterfall as they thought Squire’s riff was too “simplistic” (as if you can only find beauty or genius in a squealing guitar solo with as many chords as possible).

Squire’s inventiveness as a player is on full show here and it’s some of his best work. Complementing that we have singer Ian Brown’s hushed lyrics make way for what seems a crescendo, crashing cymbals and then we’re away.

Chimes sing Sunday morn,

Today’s the day she’s sworn,

To steal what she never could own,

And race from this hole she calls home.

Drummer Reni’s falsetto backing vocals kick in, his drumming also setting the track in full motion and steering it forward.

Bass player Mani rumbles along in the background throughout, but the driving forces to Waterfall are Brown and Squire.

The looping riff that chimes as it matches crashing cymbals and drummer Reni with his jazzy fills (the latter feature way more on tracks such as the chillout number Shoot You Down).

He’s busy at work on the high-hat and his incredible backing vocals complement Brown’s innocent, hushed style.

The band is certainly taking us on a journey here. There’s a young lady and something is happening, seemingly to escape poverty.

As Robb notes in Resurrection of British Pop:

“Waterfall rides in on that burning arpeggio. A spooked figure, it shimmers with that updated psychedelic that the band were now so adept at trading … when the acoustic guitar drops in near the end it shifts another gear, you sit back and wait for one of those glorious churning endings that the Roses specialised in but it tantalisingly goes to a fade out.

Waterfall is further evidence of the sheer depth of Squire’s guitar playing. It seems like every trick he has up his sleeve is at play here from the trademark wah wah to spine-tingling acoustics, the non-macho guitar hero. There is a total sensitivity at play here.”

Themes of empowerment abound here as this is a very uplifting and positive song. Not in classic pop sense, such as with the fast-paced She Bangs the Drums.

Instead, there’s a certain melancholia to the lyrics in Waterfall.

The Stone Roses had already shown an aptitude for such reflection as early as 1987 with the Sally Cinnamon single.

But Waterfall is an introspective number and it’s arguably the best piece of writing from the Brown/Squire songwriting partnership.

Those lyrics are soaring—they really pick you up and turn your day around:

Now you’re at the wheel,

Tell me how, how does it feel?

So good to have equalized,

To lift up the lids of your eyes.As the miles they disappear,

See land begin to clear,

Free from the filth and the scum,

This American satellites won.She’ll carry on through it all,

She’s a waterfall.

Some beautiful sentiments are in here about personal freedom. Potentially, this is a coming of age song? That and many other things, it seems.

But those closing lyrics, man. Bloody hell. Here:

Stands on shifting sands,

The scales held in her hands,

The wind it just whips her and wails,

And fills up her brigantine sails.

And then it all leads off into one of the band’s specialities—a playful, energetic outro. Squire’s acoustic guitar overlayed, a lengthier guitar solo, a crashing climax a little bit reminiscent of The Who’s chaotic ending to My Generation.

The meaning of Waterfall is up for debate. On songmeanings.com we came across one analysis from 2006:

“This is an astonishing song, great riff and those lyrics… I’m not a flag waver or anything but I think this is one of the most profoundly patriotic songs I’ve ever heard. Britain’s got its faults, its old and creaky, it lives in the past etc, but despite being almost submerged by the influence of US culture it carries on in its rickety eccentric way. The absolute master stroke is that the song is in the style of a sea shanty with Ian Brown doing his folky best to sound like a 19th century troubadour.”

We agree it’s an astonishing song. But we don’t think it’s patriotic.

The eponymous debut album is anti-Tory and anti-monarchy. A few other comments on songmeanings.com reflected this, but Ian Brown has said Waterfall is a song about a woman who’s had enough.

She takes some drugs and goes to Dover. Planning to escape the country? Or contemplate the modernisation of England?

Manchester in ’80s era England wasn’t exactly a great place to live. Quite the opposite.

In fact, the allure of The Stone Roses for many was they offered (and still do) life-affirming music despite the poverty and decay that generation faced under Thatcher.

For us it’s a song about escape. Leaving behind poverty and working-class hopelessness—there is a way out, one way or another.

As John Robb states in The Stone Roses and the Resurrection of British Pop:

“The lyrics are, according to Ian, ‘a song about a girl who sees all the bullshit, drops a trip and goes to Dover. She’s tripping, she’s about to get on this boat and she feels free.'”

Our favourite song from the band? Yes. But then there are many other classics to pick from, too, but we think this one defines the band’s genius.

Early Demos of Waterfall

There are a few earlier takes on the song that have surfaced.

Above, this example was included for the first time in the 2009 collector’s edition marking the 20th anniversary of the eponymous debut.

The band members (no reunion in sight at that point!) all gave their consent for the release of many demos. The album included three CDs, three vinyls, artwork, and a book.

And you can find a few others on YouTube, such as the 1988 demo below. This was before the band headed to London to record their debut with John Leckie.

As you can hear, the song was already fantastic in its early form.

By the time they came to properly record it in 1989, with John Leckie’s production expertise, it then entered the stratosphere to an all-time classic.

The Recording of Waterfall (happy, silly days)

Fantastically, there’s footage from 1989 of the band in action down in a London studio. In late ’88 and early ’89, they got the eponymous debut album recorded.

Whilst clearly committed to the task, the band was also committed to dicking around as much as humanly possible. Particularly The Stone Roses’ pin-up, Reni, whose silly wit is in full force throughout footage above.

The behind the scenes clips of the band in the studio first appeared on the very first Stone Roses DVD. That launched in 2004—we were at uni back then, 20 years old, and we remember watching that footage on a loop.

It’s a great insight into the band. But also a documentation of how they developed Waterfall out in the recording studio.

Notable Live Waterfall Performances

Rehearsals for the band in Lancaster on 08/06/1989 show the four members absolutely riffing off an unexpected rise to national stardom. They were on a mission.

And this is a perfect example of why The Stone Roses were so special at their peak.

Brown sounding fabulous, John Squire on form, Mani fitting in effortlessly, and a genius drummer almost dominating the show with his singing and rhythm skills.

Although Ian had been smoking all day so sounds a bit ropey at the ’89 Blackpool gig, the band’s musical abilities are nonetheless on full show.

It’s a punkier version here, but it shows off the effectiveness of the outro and how thrilling the band’s live performances were at their peak.

Particularly noticeable is the sheer physical effort of Reni’s drumming, which you can hear in the thunderous climax. On a three-piece kit, he’s going ballistic.

Better live versions exist, particularly from the legendary Glasgow Green gig in 1990. But for its impact and punchiness, we like the Blackpool effort.

On other recordings around the time, Reni’s backing vocals really help lift the song.

These recordings make us think of an NME journalist’s comments about the drummer following a live show in Amsterdam.

“Drummer Reni is magnificent. In Amsterdam, I’d watched him soundcheck for an hour on his own, slapping 17 shades of shining shite out of his kit for the sheer unbridled joy of playing.”

Heading over to Tokyo for a show on the 10th October 1989, the take on Waterfall is again quite punchy and punky.

From the band’s various reunion gigs, they really hit their stride properly from 2013 onwards and particularly in 2016 (shortly before calling it a day again).

But it shows a band working well together, Brown’s voice sounding excellent and Reni (after a tentative start after returning to drumming) now in full flow.

The Stone Roses was very much like The Who with live performances.

Whilst the studio albums were polished and magnificent (and that does include some of the best bits from the band’s sophomore album Second Coming), their live performances were a different beast entirely.

And whilst Brown’s vocals could be a bit all over the place, his stage presence never did falter.

At their collective peak, the band was indeed magnificent. All four members working in unison to deliver this work of genius.

Don’t Stop and the Art of Reversing Waterfall

On a final note, the band had a habit of taking their songs and then reversing them. They found they could add lyrics over that and have another great track!

Don’t Stop is one such example. It’s Waterfall reversed, with Brown’s cryptic lyrics and new singing added over the top for excellent effect. The singer’s verses don’t make much sense as he was riffing off his garbled reversed lyrics from the other song.

Reni’s drums from Waterfall are also removed as he added in overdubs to the mix, with his usual fantastic backing vocals added into the mix.

However, Don’t Stop was a track the band didn’t perform during its 1989 heyday. It never appeared on a live set, although it can be heard playing prior to the main performance at the likes of the Blackpool 1989 gig.

When the band reformed in October 2011 a big surprise was Don’t Stop suddenly emerged into the set! We particularly like this live performance from Village Underground in London.

That really highlights the band’s reformed circa 2012 era strengths. We think their best shows were actually in smaller venues like this.

Not sure why, as most of their big venue performances were great, too. Maybe as it’s because all the tinny smartphone recordings could pick up the sound quality better.

Although Brown would frequently chastise the audience for recording on their phones, urging people to enjoy the moment instead. Well, we’re glad some of this was recorded for posterity.

Great post! My (musical) friend and I were just talking about Stone Roses a few days ago…

LikeLiked by 1 person

I meant friendS.

LikeLike

Friends… as in Ross, Rachel, Chandler, Joey, Monica, Phoebe, and Gunther?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Funny that you say that (coincidences abound): earlier this week my girlfriend and I started watching Friends season 1! X–D

But I have a couple of friends with which I often talk about music, and those are the friends I had in mind.

By the way… Gunther???

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gunther is THE best Friend. There should have been a spin off!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I really love this. It reminds me of the Proclaimers 500 Miles! Enjoyed.

LikeLiked by 1 person

If you watch the video for 500 Miles it’s the two brothers juddering around in quite hypnotic fashion. Get Ready also featured in Dumb and Dumber. Which is fun.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such fun.

LikeLike

Walking 500 miles, and then walking 500 miles more, isn’t fun.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s 1000 miles. Wow!

LikeLike

I still feel walking 500 miles is something of an over requirement.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would need a great pair of Nike’s!

LikeLike

I would walk 500 miles for a really nice cake.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yummy, me too. Or I could just go to the bakery. I’m not baking a cake.

LikeLike

Oh yeah, kind of forgot about shops. There’s not a shortage of cake, thankfully.

LikeLike