One of the most popular pieces of classical music, Pachelbel’s Canon (in D) was written by Johann Pachelbel (1653-1706). The German Baroque musician was wildly popular during his day, but it’s this one piece of chamber music that’s ensured his lasting legacy.

Whilst enormously popular now, the piece had fallen into obscurity for centuries. It’s only in the modern era that’s in come back to prominence. And because that sort of stuff always interests us, we went off and researched it all for this feature. Innit.

From Obscurity to Global Fame: Pachelbel’s Canon in D

There it is, one of the most famous pieces of music worldwide. The thousands of magnificent classical pieces prove people from the past weren’t all knuckle-dragging savages.

And yet the piece did lay formant for hundreds of years, only coming back to public light again in 1919, before a 1968 arrangement fuelled its resurgence. We’ll get to the history a bit later, for now we’re looking at what an accompanied canon is. As in music it’s a counterpoint-based melody that has imitations and often repeats. The opening melody is, essentially, the leader in the piece of music.

Then a chase begins, with the subsequent stuff being the followers playing the same melody. Us musical laypeople can think of it as an echo, such as with the French nursery rhyme Frère Jacques and how it loops over and over.

What Johann Pachelbel did is more complex, adding in a cello (and some versions have a harpsichord) to act as a rhythm section. This keeps time, allowing the violinists to riff off each other, almost like they’re playing a game of cat and mouse.

It’s called a Romanesca (melodic-harmonic formula) that was very popular during the composer’s era.

The piece is famous for its violins, which form a triple canon (a “true canon at the unison”). The three violinists play the same music, but start at different times. Like this:

- Violin 1 starts the main melody with a staggered entry

- Violin 2 enters two bars later

- Violin 3 enters another two bars later

For the listener, we hear three different parts of the same melody playing at different moments (but all at the same time). That’s why the piece has its harmonic, intertwined layers and complexity.

Pachelbels’ Canon (Lost and Found)

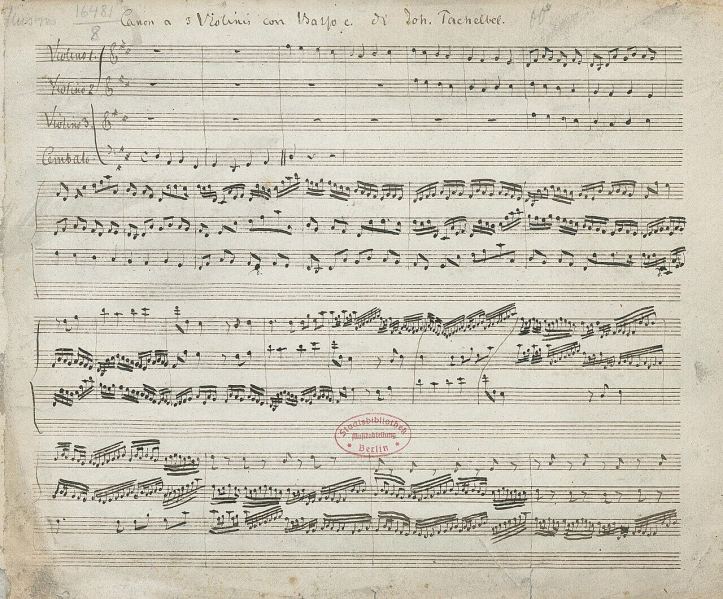

That there above is a genuine page from a 1648 manuscript of the piece (the only one in existence). It’s the oldest surviving copy of Pachelbel’s work and rests in Berlin State Library.

The composer was born in Nuremberg (1653). Composer Johann Mattheson provides contemporary sources (Grundlage einer Ehrenpfort—Foundation of a Triumphal Arch: 1740) and noted Pachelbel was highly gifted from childhood.

He studied at University of Altdorf and was so impressive with his academic results he allowed to study despite the course being full (an extra space, just for him). He was incredibly successful, unlike the likes of Mozart, mainly in chamber and organ music.

The guy was no one hit wonder, despite most people being unable to name other work than the Canon. But here’s another below: Chaconne in F Minor (PWC 43) on a big old grand piano.

Other famous pieces include Hexachordum Apollinis (a collection of six arias) an Toccata in E minor.

But yeah, no escaping it’s the Canon he’s most famous for. It was completed some time between 1680 and 1706, which is a big old gap there. Fact is, there’s no historical record (yet) of when it was completed or the circumstances for it (like, if it was for a wedding or something).

But what did happen is, as the centuries ticked by, the piece fell into obscurity for 300 years.

It’s thanks to Gustav Beckmann that the piece was rediscovered. Writing about Pachelbel’s vast selection of chamber music, the Canon was included it in Johann Pachelbel als Kammerkomponiſt (1919). Music scholar Max Seiffert was Beckmann’s editor and eventually published an arrangement in 1929 (Canon in Gigue).

That’s, apparently, quite a different version to what we’re used to now.

The next step for the piece was the landmark moment. French conductor Jean-François Paillard made a recording in 1968 (The Paillard Recording), which led to a surge of its popularity across the 1970s. With all that new technology and the like, in TV, radio, and film, the piece was much more accessible to the public.

It was then used as the theme to the Oscar winning 1980 film Ordinary People, directed by Robert Redford, and has only grown in popularity since.

It’s now more popular than Wagner’s Bridal Chorus for wedding days and the chord progression has been nicked by many pop/rock stars for their songs.

Pachelbel’s Canon in D: A Smalin Visual Representation

After discovering Stephen Malinowski’s classical music visualisations in 2012, we’ve been obsessed with them ever since. We’ve overed Pachelbel’s Canon smalin visualisation before, but what to include it again here. It’s a ChromaDepth 3D detailing.

What we particularly like about this banger of a song (i.e. piece) is the interplay between violins. This is shown very well from 1:57 on the above, following the red line before the green merges with the canon from the 2:07 mark. Then from 2:15 the blue joins into the mix and you can see the free flowing nature of the canon working in unison.

That’s all the canon stuff in action, the violinists riffing off each other playing a melodic version of follow my leader.

Pagagnini: Playful Mockery of Repetitive Cello

It’s only odd when you look out for it, but Pachelbel’s Canon has a looping cello. The musician must repeat the same eight notes over and over. All whilst the violinists get to run riot with their melodies. This is the bass stuff:

D-A-B-F#-G-D-G-A

It’s become a running joke in classical music circles, which the Spanish comedy troop Pagagnini spent years playfully running rings round (the above performance is from 2008 at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival). It was established by virtuoso Lebanese violinist Ara Malikian, that’s the dude with the big hair on the left.

Pagagnini still seem to be touring with two of the original members and have a bunch of shows across early 2026 (should you be in Madrid or Valencia). Good fun then and we’ve been enjoyed that video since 2010, which we think makes classical music fun and accessible for all ages.

Plus, those guys are hellish good players, non? They also show there is humour to be found in classic, not an arena of stuffy old people stroking their beards and donning a monocle.

It’s always intrigued me that, not too many years ago, ‘classical’ music was considered cultured and sophisticated, whereas ‘rock’ music (‘ptooey’) was performed by uncultured animals whose barbaric noises did not require training to make. Whereas in fact both used the exact same 12-tone scale chord progressions, keys etc, which probably explains why the – er – canonical Pachelbel progression is used by Maroon 5, Bananarama (Stock/Aitken/Waterman), Oasis, Taylor Swift, Joe Jackson, Green Day etc. And Tenacious D. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_lK4cX5xGiQ I am prepared to bet that Herr Pachelbel never did a performance like that one. Though we don’t know what he got up to in his spare time…

LikeLiked by 1 person

How much are you willing to bet? Maybe Pachelbel had a punk phase in his early 20s and went around gobbing at everyone, Sid Vicious style. I’d bet about $1 NZD that may have been the case.

There’s a book in that: Classical Musicians Behaving Badly. Foreword by Keith Richards.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now that’s a thought. Or a movie? Liszt’s been done (totally accurate 1975 docco by Ken Russel), so what about ‘Pachelbel breaks the toilet in EMI head office and loses a contract’, thoughtfully retitled ‘Pachelbel gobs on everybody’ by the marketing department?

LikeLiked by 1 person

If that comes with an AI generated poster and trailer I’m all in. I did watch Ken Russell’s Tommy a while about during my peak Who years and can’t say that went very well for everyone. In the So Bad It’s Good territory, though.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I match your ‘Tommy’ and raise it by one ‘Lisztomania’. Health warning: this is 2 mins 54 you won’t get back, though Mr Wakeman is very funny (as usual – I’ve seen him perform live & he’s a brilliant raconteur). https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aOKrSPFEK4g&list=RDaOKrSPFEK4g&start_radio=1

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wow not seen Lisztomania that looks… yeah, think a few drinks before seeing that in 1975 and that would’ve been film of the year. Better than Jaws, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest etc.

LikeLiked by 1 person