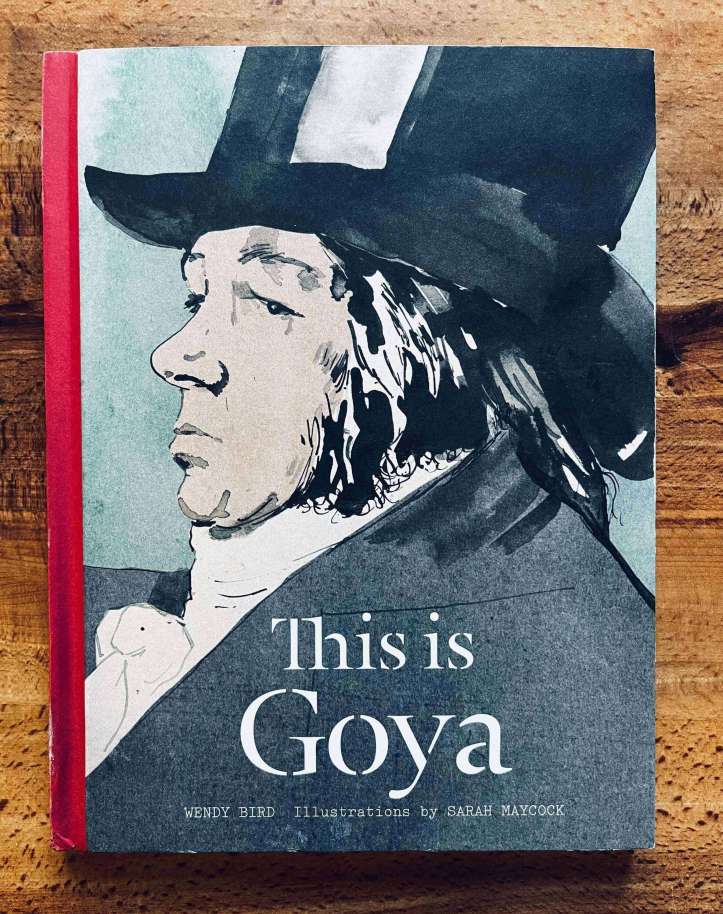

Part of a series of introductory works (we already covered This is Caravaggio), this time we’re examining the artistic life of one Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes (1746-1828).

This is Goya was published in 2015 and was written by Wendy Bird.

The work briefly covers the life and times of Goya, widely considered the most important Spanish artist of the 18th century. He was famous for depicting social upheavals, followed by the Black Paintings series notorious for displays of increasingly disturbed imagery.

From Landscapes to Hellscapes in This is Goya

“Goya’s art rises above the chaos of his times and signals the real revolution of personal expression and independent spirit that would be the generative force behind the Modernist movement in art.”

There aren’t any chapters in this work, it’s more a free-flowing demonstration of Goya’s artistic developments. His style was influenced heavily by social events, most notably when Napoleon went off on one with his armies.

What’s fascinating with his canon is the progression it takes from more carefree and playful to heavily disturbed (the latter playing out in his final years).

There’s the likes of Caza con reclmao (Hunting With a Decoy from 1775), Goya’s first commissioned work. He was good enough to then receive royal commission and he began creating portraits for the likes of Count of Floridablanza José de Moñino in 1783.

As ordinary as that portrait is (of some snobbish monarch from the past), the chance to paint it meant a big deal for Goya’s career.

Thus, 1783 was a turning point for the artist. He was soon invited to complete work for Prince Don Luis, one of the first esteemed gentlemen in all of Europe to own a zebra. The prince had been exiled by King Charles III, which is how Goya got his foot in the door.

By 1786 Goya was court painter to Charles III and he retained his position after 1788 when Charles IV took over.

His work from that time is pretty dull, really, as it depicts boring, overprivileged lives of ruling monarchs standing around looking posh. It was work Goya needed to complete for a paycheck and career, with the added bonus it lifted his social standing and reputation.

Bubbling away beneath that professional veneer was something much more impressive.

Take this 1797 piece El sueño de la razón produce monstruos (The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters). This followed a 1792 illness that left him deaf (potentially caused by lead poisoning), leading to noticeable changes in his work.

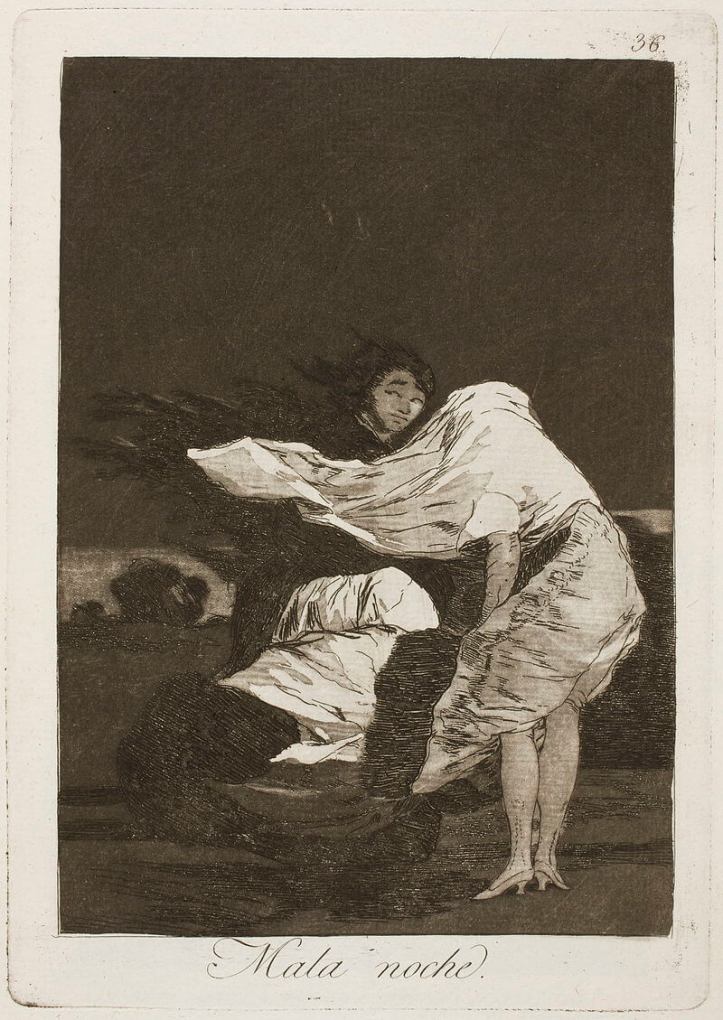

This piece was part of a satirical Los Caprichos (The Caprices) set of 80 prints and published in 1799. These were an artistic experiment—satirical takes on Spanish life of the time.

The whole set is like that, consisting of vivid whites and dark greys. For the time, these were merciless critiques of Spanish life and actively mocked nobility and religious figures.

Only a fortnight after this set was published, Goya hastily withdrew the works from the public whilst fearing the Spanish Inquisition. He later sold them all to the latest King in 1807 in return for a lifetime pension.

A year later and life in Europe took a turn for the worse, with this going on to significantly influence the artist’s style and legacy.

Goya’s Coverage of Napoleonic War

Napoleon’s French army invaded Spain in 1808 to trigger the 1808-1814 Peninsular War. The famous Third of May 1808 painting above (El tres de mayo de 1808 en Madrid) was completed in 1814.

The purpose of the piece was to commemorate the Spanish army’s bravery against Napoleon’s forces. Goya suggested the piece to the provisional Spanish government, only shortly after the end of French occupation (Napoleonic Spain from 1808-1813).

These commissioned works, often depicting bloody scenes of warfare and executions, continued up until around 1819.

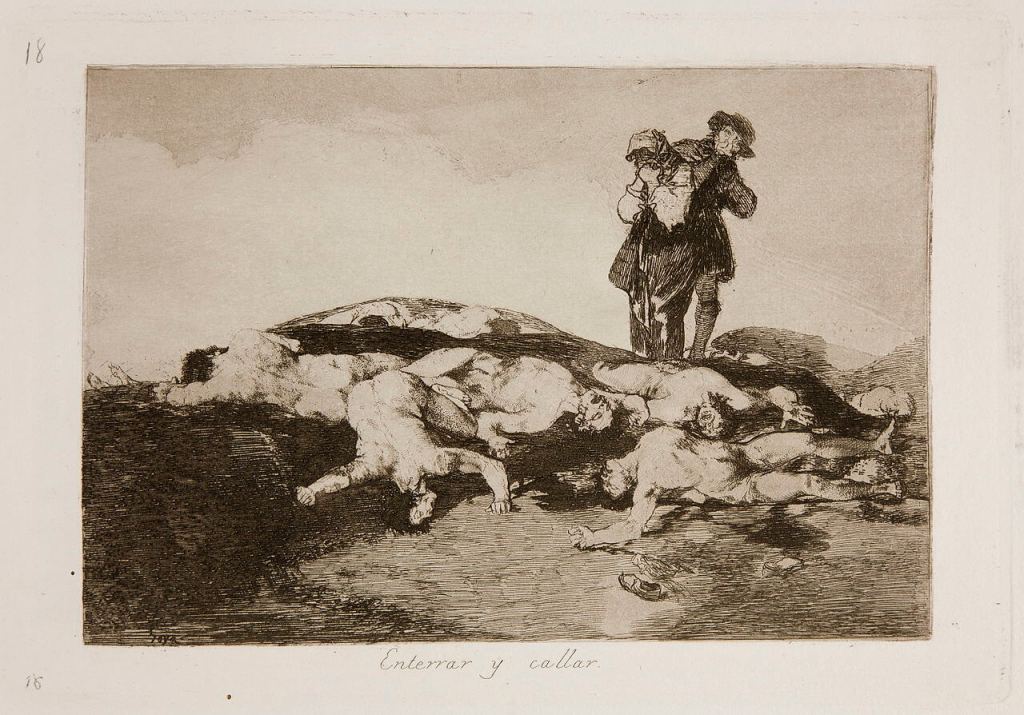

However, between 1810 and 1820 he created another series of Los Caprichos prints (82 of them) called The Disasters of War. The title alone indicating how French occupation affected the artist.

The series is considered a visual protest against war.

You can look up these pictures online and they include the likes of For a Clasp Knife where a garrotted priest is seen on the verge of death. It’s a brutal series, but in it we can find the cyclical nature of human activities.

Piece 18 is Enterrar y callar (Bury them and keep quiet). It depicts atrocities and starvation. In fact, it’s worryingly similar to the images that emerged in the aftermath of The Holocaust after 1945.

82 images like this. A harrowing set, but beautifully depicted and, again, a clear indication of the toll it had all taken upon Goya’s state of mind.

Perhaps it isn’t surprising that, from around 1819, records of Goya’s activities kind of grind to a halt. It is known he bought House of the Deaf Man (Quinta del Sordo—already called this when he moved in) in February 1819.

Whilst completing prints for The Disasters of War, he became extremely ill. After recording from that in early 1820, he became reclusive and began his iconic drawings across the walls of his home.

Notes on the Black Paintings

A while back we did a feature on Goya’s Saturn Devouring His Son (circa 1820). It’s one of 14 paintings, most of which were completed between 1820 and 1823.

These became known as The Black Paintings.

These are all dank, disturbing, and deeply macabre. This has led many art enthusiasts to presume Goya was either losing his mind or in a state of severe depression. Covered in other works from the This Is series, we must note Caravaggio had a similar issue. Due to his psychotic lifestyle, many enemies were out to behead him—the result was his artwork became increasingly desperate and disturbed.

Was it the same for Goya? His walls became an assortment of bizarre phantasmagoria and wildly disturbing imagery. None of which was intended for public view.

Or was it just creative expression and exploring new territory? One of his paintings was another self-portrait, now as an old man holding two walking sticks, with the painting named Aun aprendo (I Am Still Learning). That was in 1826.

Whilst it’s tempting to romanticise this phase of his life as a tortured genius living alone and losing it, friends did note the man was happy enough. When not painting on his walls, he continued with normal portraits—one was of his grandson Mariano.

A friend of Goya’s wrote in an 1827 letter (the year before the artist’s death):

“He is fine, he keeps busy with his sketches, goes for walks, eats and sleeps the siesta…”

Not totally barking mad, then, more still intrigued by creative opportunities. His wall paintings, perhaps, a cathartic release on the more haunting memories from decades earlier.

Closing Thoughts on This is Goya

A deliberately condensed work, consisting also of illustrations by Sarah Maycock, we must say this is great little book.

As an intro to Goya’s incredible life and times, it’s a fine explainer for how one man depicted Spain’s development from pre-to-post Napoleonic era. Before then descending into a strange world of isolation and, potentially, madness.

We got this on offer at Waterstone for £1.99. Money very much indeed well spent, with intriguing illustrations to bring to life Goya’s dramatic times.