In The Collected Schizophrenias (2019) by Esmé Weijun Wang we had a first glimpse into the much misunderstood world of schizophrenia.

As a mental illness, it typically strikes fear into people. People view it as a different type of humanity—almost alien.

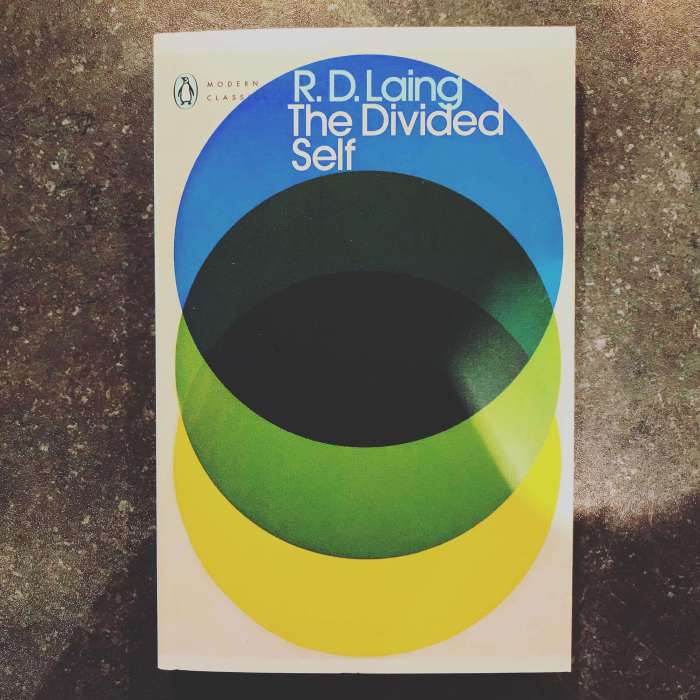

But psychiatrist R.D. Laing (1927-1989) set out to challenge that notion with a landmark work in 1960, which was The Divided Self. Here’s an overview of his study.

The Divided Self: A Existential Study in Sanity and Madness

Along with medical classics such as Dr. Oliver Sacks’ The Man Who Mistook His Wife For a Hat (1985), The Divided Self was a landmark work in the 20th century.

Laing’s goal was to make madness understandable—to provide a humane consideration on the struggles with those previously dubbed as “crazy”.

In the 1964 preface to The Divided Self, Laing noted:

“A little girl of seventeen in a mental hospital told me she was terrified because the Atom Bomb was inside her. That is a delusion. The statesmen of the world who boast and threaten that they have Doomsday weapons are far more dangerous, and far more estranged from ‘reality’ than many of the people on whom the label ‘psychotic’ is affixed.”

Using an existential-phenomenological framework (the study of consciousness and subjective human experiences), this allowed Laing to consider individual lives.

That’s rather than just standard conformity and other social behaviours.

And in The Divided Self, his main argument is psychosis isn’t a medical condition. It’s an outcome of the tensions between two personas:

- Our true selves, the private identity.

- The false “sane” self we present to the world to fit in.

His point being that alongside ontologically secure people (with a stable mental state), those with schizophrenia use various “normality” strategies to avoid losing their way in society.

Based on his research, Laing laid out a psychodynamic model on how the human mind enters psychosis and schizophrenia.

Alongside all the philosophising and theorising, he cut through everything to promote the real issue. People’s lives left in chaos due to mental illness.

Chapter 8 is “The case of Peter”, which is a clear demonstration of the issues many people have to face with this condition.

Peter came to Laing believing he was kicking up a foul stench, although this wasn’t the case. Only he could smell the non-existent odour.

During assessment, Peter revealed he grew up believing he was an inconvenience to his parents, both of whom showed little interest in him.

“His own feeling about his birth was that neither his father nor his mother had wanted him and, indeed, that they had never forgiven him for being born. His mother, he felt, resented his presence in the world because he had messed up her figure and damaged and hurt her in being born. He maintained that she had cast this up to him frequently during his childhood. His father, he felt, resented him simply for existing at all, ‘He never gave me any place in the world…’ He thought too that his father probably hated him because the damage and pain he caused his mother by his birth had put her against having sexual intercourse. He entered life, he felt, as a thief and criminal.”

Apparently, his parents treated him like “he wasn’t there”, with his mother displaying many self-obsessed signs of a narcissistic personality disorder.

The result for Peter was, by the time of his young adulthood, he’d became highly self-conscious, anxiety-ridden, and plagued with worthlessness.

He also felt disembodied and strived to be “seen” as existing by those around him, all the while acting his way through his life to appear sane.

His act worked. He appeared to be fitting into society normally, even landing a coveted office job (remember, that was quite the novelty in the first half of the 20th century).

And, yet, Peter couldn’t think beyond his pointlessness. Laing noted:

“The body clearly occupies an ambiguous transitional position between ‘me’ and the world. It is, on the one hand, the core and centre of my world, and on the other, it is an object in the world of the others. Peter tried to uncouple himself from anything of him that could be perceived by anyone else. In addition to his effort to repudiate the whole constellation of attitudes, ambitions, actions, etc., which had grown up in compliance with the world, and which he now tried to uncouple from his inner self, he set about trying to reduce his whole being to non-being; he set about as systematically as he could to be become nothing.”

And when Peter did something “normal” people do (as in, he dropped his pretence), it had consequences:

“He had severed himself from his body by a psychic tourniquet and both his unembodied self and his ‘uncoupled’ body had developed a form of existential gangrene.”

And that’s why Peter believed he was kicking off a fearful smell.

To demonstrate what this type of experience can look like, here’s an interview with a young man (and it’s not Peter, to be clear) in 1961 in a state of catatonic schizophrenia.

When The Divided Self was published in 1960, it was still a time when “the crazies” (a nod to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest there) were bungled out of the way from society’s prying eyes.

These people were irrelevant; or frightening.

And yet Laing revealed this is misguided terror and did so with a humane explanation for how the mentally ill can lose their way.

When you’re disembodied, “not you”, and can’t relate to the world… where can you turn? Are you even alive?

It’s a just and sophisticated society that’ll understand this situation and help patients find themselves and exist in society.

At least for us, that’s the empathetic heart of The Divided Self.

About R.D. Laing

Ronald David Laing was a Scottish psychiatrist whose research on mental illness primarily focussed on the nature of psychosis.

Whilst many of his peers were using chemical and electroshock treatments to help with mental illness, his route was formed by his study of existential philosophy.

The Divided Self made him a popular cult figure, especially during the Sixties counterculture movement.

By 1965, he’d co-founded and was chairing the UK charity Philadelphia Association to help with mental suffering.

His reputation is still strong and continues to grow, especially now the world is more aware of mental illness and how it’s far more commonplace than ever thought.

The renewed interest in Laing’s work led to a 2017 film Mad to Be Normal, in which David Tennant starred as the psychiatrist.

In his personal life, Laing was open about his own struggles with alcoholism and clinical depression. He diagnosed himself for both conditions.

However, by admitting these issues (on BBC Radio in 1983) it meant he lost his medical license.

Laing also had multiple marriages and fathered 10 children.

Some of his children have come forward to note he was so busy being a psychiatrist, his commitment to his family wavered.

Ultimately, Laing died of a heart attack during a game of tennis in 1989. He was 61.

You might want to read “Knots” a difficult book as one must be willing to follow Laing in his spiral of descent. Interestingly smelling odors that others do not can be a symptom of a brain tumor. Thank you for a most interesting narrative on R.D.Laing.

LikeLiked by 2 people

What? This is such an intellectually finessed answer that I am in horror that “Oron hasn’t answered you.

Just goes to show who is mentally superior!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Hee hee! He’s discovering that Laing was one effed up dude.

LikeLiked by 1 person

… and you are one gowned up gal! xoxoxo

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks to you Meece x🐭🐭x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah, but he was Scottish. So, that’s what haggis does to you I suppose.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I suppose. Goes to your head makes you wonky, esp if you add amphetamines.

LikeLike

Haggis and paracetamol? Yeah, that’d mess you up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’d think haggis would be enough !

LikeLike

It’s more than enough! Very filling, it is.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As tempting as haggis is I have to think of those poor cows. Heartbreaking.

LikeLike

It’s sheep that it affects. Cows are the burger wagons. It’s all very nasty.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Omg! Sheep 🐑, that’s heinous.

LikeLike

Sheep truly are heinous individuals. Don’t believe their baaas.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m such a sucker, they always get me where their sad eyes and baas.

LikeLike

They are quite docile and cool animals really. Baa. Baa! Kind of like goats. Except goats are angrier.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lambs are my faves.

LikeLike

Jodi Foster was good in that film.

LikeLiked by 1 person

She is always good. What a scary movie but she was excellent in it , I have seen it several times. I like scary movies.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jodie Foster. I got her name wrong. That e is all-important! Wouldn’t be famous without that.

I watched Mandy recently, with Nic Cage. That was scary.

LikeLike

Going to have to have a go at that. Sounds gory.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is is mega gory. Phantasmagoria! Plus, Nic Cage going full Nic Cage in the second half of the film. Bon.

LikeLike

I watched the trailer. Nic at his gory best!

LikeLiked by 1 person

He goes full mental. Is great.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yeah…….

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hath responded! It’s interesting this review has become about smells now, which is an issue I often breach on Agony Aunt. Smell is important, you see?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Smell… stench… stink… odour…. perfume…. what exact olfactory experience are we focused on?

LikeLike

The olfactory experience of “Ewwwwwwwwww!” You know the one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A female sheep?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Finally, I got one!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you kindly for the recommendation, one shall indeed check that out. This is an important lesson for us all to really check on our smelling abilities.

LikeLike

My smelling ability is so Acute it’s has been documented in the AMA under Rare Diseases.

LikeLike