Duff Cooper’s classic biography Talleyrand (1932) is an impressive feat of research. Alfred Duff Cooper, 1st Viscount Norwich, GCMG, DSO, PC was a Conservative MP from the UK, one greatly respected by Sir Winston Churchill.

He completed this work on Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord (1754-1838) whilst a politician, working slowly to piece together Talleyrand’s dramatic life. The result was impressive enough to meet with widespread success, with the work still in print heading for a century after its first edition.

The Decadent Life Experiences of Diplomat Talleyrand

“Revolution is a symptom of grave political disease, and, unfortunately, it is contagious.”

Cooper’s biography is classic in its structure, following his adolescence, time with the church, rise to loftier positions, and all whilst documenting the political battles in France.

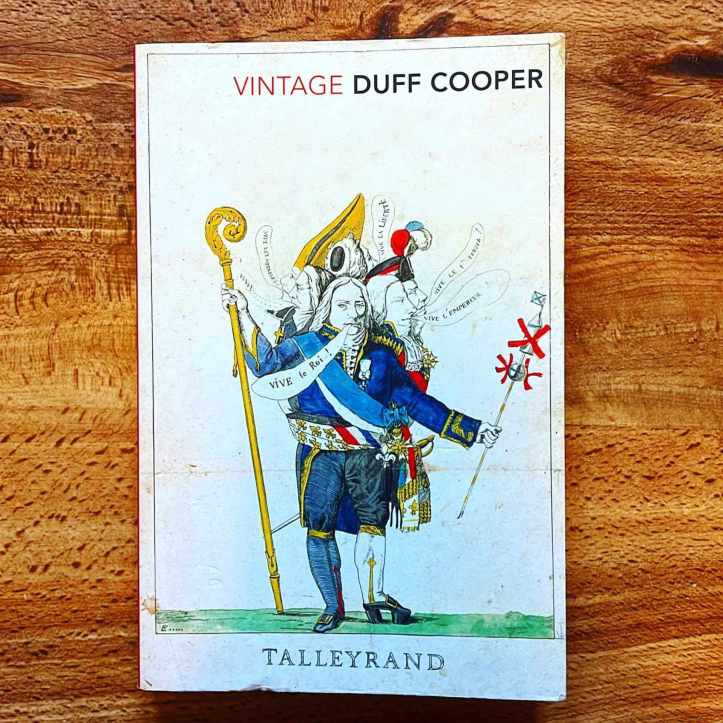

Talleyrand was born in Paris to an aristocratic family and would rise to become Napoleon Bonaparte’s chief diplomat. Here’s a portrait of the man, the myth, the legend.

Popular with his peers, Talleyrand was also a bit of a womaniser. He didn’t want a career in the church and so had one eye on politics, an avenue that opened for him as France’s regal situation descended into bedlam.

The French Revolution began with The Estates General of May 1789, ramped up with the Storming of the Bastille on 14th July 1789, and ended in November 1799 with the Coup of 18 Brumaire.

It was a very complex political environment and there’s where Duff Cooper excels as a historian. He sifted through all the information and presents it clearly, notably alongside how Talleyrand’s antics played out during that time.

“Meanwhile the Revolution was moving daily in the direction of war. The same policy recommended itself to the various parties for different reasons. The extremists wanted, in the worlds of Merlin de Thionville, ‘to declare war on the kinds and peace with the nations’—the Girondins believed that war would mean the downfall of the King and the logical fulfilment of the revolutionary ideal. The Feuillant Government hopes that war—a nice, small war directed if possible only against the Elector of Trier for having been too kind to the émigrés—would restore their credit, enable them to remove the King from Paris and continue to carry on his Government with the assistance of the army. The King and Queen, who were now very near to despair, saw in the advent of a foreign invader that last hope of deliverance form the hands of their own people.”

He played a great deal in the 1799 coup d’état, with the French Consulate government established after all the political upheaval. Napoleon appointed him to be Foreign Minister and also later forced Talleyrand into marriage in 1802.

Talleyrand was a shrewd diplomat and a ready wit. Cooper documents this, highlighting a man who wasn’t afraid of challenging peak authority. He said this after Napoleon had a temper tantrum.

“What a pity, such a great man and so ill-mannered.”

As the book covers, the diplomat did eventually tire of Napoleon’s efforts and betrayed him. This was due to concerns the empire builder would, ultimately, destroy France. He retired from Napoleon’s ministry in 1807 and began to accept bribes from Austria and Russia and disseminated his former leader’s secrets.

He eventually wen on to found the France’s National daily newspaper in 1830 (which was eventually outlawed in December 1951 after Napoleon III’s 2 December 1851 coup) and became ambassador the UK from 1830-1834.

“When Talleyrand signed his resignation in November 1834 he had still three and a half years to live. It would seem that during these years he enjoyed as great a measure of happiness as ever falls to the lot of those who react extreme old age. His health was failing and his limbs were crippled, but his senses of sight and hearing were undiminished, and the pleasures of conversation remained with him to the end. He had survived his generation; the companions and the loves of his youth were dead; but he never lacked congenial society, and there was always at his side the woman to whom he had been devoted for twenty years, who, at the age of forty, retained her beauty, and whose daughter, the child Pauline, his ‘guardian angel’ as he called her, shed an atmosphere of innocence and pure affection over the closing days of his life.”

It was an incredible, dramatic life filled with revolution, war, and political meandering. A world that doesn’t exist now, instead we have the joys (*ahem*) of capitalism and business shenanigans. But Duff Cooper covers the lot in finite detailed, with a level of research befitting a methodical and precise man.

Yet there is the matter of how he delivers all of this information. Indeed. Rather.

Notes on Duff Cooper’s Historical Writing Style

The main issue we have with Duff Cooper’s Talleyrand is his writing style. It’s very much of its time, but before we knew anything about the guy we could tell he was an overly educated Conservative. The book is longer than it needs to be simply to allow him to finish a sentence. It’s always stuff like this.

“To obtain the admiration of women is the ambition of most men, and those who achieve it easily are apt to believe that their success is in some way a proof of their intelligence, forgetting that it is not always intellectual superiority that makes the strongest claim on feminine regard.”

Above is a classic example of what you’re getting into when you read this book. You can pick any random page and paragraph, Cooper is there doing his thing. Clever and dry wit at times, but regularly teetering on the edge of prolixity.

As a bit of playful mockery, below is us doing a Duff Cooper.

“It is clear to see whence that wherein, pertaining to its own accord; in accordance to, what with, the machinations from which there were, not by accident, but in certain proprietary inaction, predicated on by happenstance, the circumspect need for (but not contained by impecuniousness), pre-dating the existence of, or non-existence thereof; and by which means the possession of need within Talleyrand; prone to bounteous imbibement of vintage respirate or labyrinthine bouquet, liquid manuscript of whispering lushes and ancient terroir singular in its pursuit downward, spiralling of Talleyrand’s guttural passage and bruised harvest of soul; of which, therefore, there was plentiful pleasure in the consumption forthwith.”

Or in layman’s terms.

“Talleyrand enjoyed wine.”

It’s noteworthy that George Orwell’s essay Politics and the English Language (1946) listed six rules for good writing and they hold up well to this day. One of which is to not use big words to try and sound smart. Be concise, get to the point.

Despite our reservations on Cooper’s writing style, it does lend an air of absurd grandiosity to Talleyrand’s life story. Almost like there’s a heroic fanfare blaring away at the start of each chapter.

But given there’s 300 pages to get through, you may need to take the odd breather. It feels very much of its time.

Addendum Alert! The Life and Times of Duff Cooper

Born on 22nd February 1890 in London, Alfred Duff Cooper (1st Viscount Norwich) GCMG, DSO, PC, was the son of high society doctor Sir Alfred Cooper (1843-1908). His father served the upper classes specifically for sexually transmitted diseases, which we’re sure was a spiffing job. What, what.

His mother was Lady Agnes Cecil Emmeline Duff (1852-1925) a descendant of King William IV.

Duff Cooper attended two prep schools, during which time he was depressed, then went to the infamous Eton College (formative ground for many over-privileged Conservatives).

He spent six months on the Western Front during WWI out on the battle lines and was noted for his bravery. After the war, his political career ran from 1924 through to 1939. However, Churchill appointed him the Minister of Information during WWII from May 1940, before moving to Singapore as Minister Resident, then became Ambassador to France in December 1943.

His standing was so strong he wasn’t replaced by the Labour government in 1945, despite the political party’s election win.

Duff Cooper was very busy, then, but still found time to piece together Talleyrand in time for its 1932 publication. His cousin, Rupert Hart-Davis (1907-1999), happened to be a publisher and could blast out the work to the public (it was a successful history book, too).

There was a great deal of privilege at play in all of this for Duff Cooper.

A lot of Conservatives don’t view it as privilege, more a God-given right, they just worked hard enough, or they deserve to benefit from their parent’s “hard work” etc. etc.

But to Cooper’s credit the book is very good and well worthy of its status. It’s also clear he was dedicated to his various government roles and took everything very seriously (unlike many modern Conservative MPs).

He retired from his Ambassador to France role in 1947 and spent the rest of his life in France. Throughout his adult life he struggled with excessive eating and drinking, which led to his early death on 1st January 1954. He was 63.