We’ve always been intrigued about people living in difficult circumstances, facing disabilities or illnesses. We guess as we got an autism diagnosis a few years back, having lived uncertainly up until 2022, this has been why.

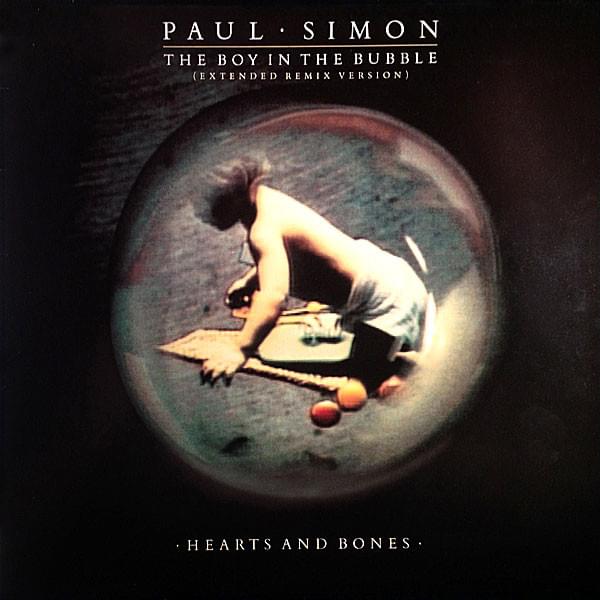

As with the story here of one David Phillip Vetter (1971-1984). It’s a sad one, but also one you’ll already vaguely know if you’re a fan of Paul Simon.

Vetter had severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) and medical professionals in the ’70s created a unique containment system with which to keep him alive. And that’s where he spent his life—in a plastic bubble, minus his immune system, as his family hoped for a cure.

David Vetter as the The Boy in the Bubble

The Boy in the Bubble is the opening track on Paul Simon’s classic Graceland (1986). It’s a direct nod to David Vetter and other news stories and events from the late ’70s and early ’80s—”this is a long distance call“.

Vetter had died in February 1984, but his story hinted at the potential groundbreaking future for humans. That someone could live in a containment unit for 12 years was part of Simon’s acknowledgement of technological advancements humanity was embracing.

We’re not medical professionals, but SCID appears to be a more extreme type of HIV/AIDS. Patients with this genetic disorder are extremely susceptible to infections and pathogens, with any exposure to normal daily life soon fatal.

With this barely existent immune system, young David Vetter entered a family already suffering loss.

His parents (Carol Ann and David Joseph) had a son called David Joseph III who also was born with SCID and died at seven months old. They decided to have another child and, unfortunately, the risk brought with it the genetic disorder.

Born on September 21st of 1971, the only medical assistance of the day was containment and isolation—a plastic bubble.

This also had to be a sterile environment, which the baby would be in until a bone-marrow transplant could be achieved. This plastic cocoon bed was ready and waiting for David Vetter when he was born and into isolation he went, gaining media attention in the process and becoming the baby in the bubble.

Everything that went into his increasingly large cocoon (food, diapers etc.) was sterilised—placed in a chamber of ethylene oxide gas for four hours, then left for one-seven days before it could be added to Vetter’s home.

This became his life, he never left the thing, and somehow had to prevail with his bizarre situation.

The Bubble Boy Found His Feet

As he grew older, Vetter’s containment complex grew in size until it was quite an advanced little area. This was located at hospital, but his parents also added a unit at their family home in Texas.

He could only visit for several weeks each year in his parent’s unit, the rest of the time he was in the close care of Dr. John Montgomery and a wider medical team.

The US media took a great deal of interest in this and news items continued to pop up, as with the below from September 23rd 1981, with Vetter remaining a minor celebrity.

You can see the young lad in a kind of spacesuit there. That’s because, in 1977, NASA took an interest in his case and specifically developed it for him.

A long hose could attach to his bubble unit and allow him to go wandering around outside for about eight feet. However, this didn’t seem much fun for him as he apparently only used it a handful of times. NASA provided him with a larger spacesuit as he grew older, but he decided not to use it.

If NASA was getting involved, it’s a clear indicator of how prominent a medical case the young boy was.

The interest had been running before he was even five, including a made for TV film production of Vetter’s life story. This starred a young John Travolta. It was called The Boy in the Plastic Bubble and launched in 1976.

It’s now on YouTube and, generally, looks like pretty awful. It seems to be a spectacle piece on what Vetter could expect as he got older (in not very accurate fashion).

This romanticisation of the SCID condition, and Vetter’s case, was part of a strangely cosy sensibility casual observers took in the story. How the young lad was apparently getting by, doing his best, putting on a brave front, laughing and smiling.

It was over a decade after his death that more details emerged about the, as expected, actual psychological struggles he endured during his brief life.

Notes on David Vetter’s Personality

Confined 24/7 to life in a plastic bubble, this was a very odd (and tragically brief) life he led. Sterilised toys were provided to him through plastic gloves attached to the sides of the chamber.

Dr. John Montgomery and Vetter’s parents wanted him to lead something of a normal life. But, fact is, he couldn’t go outside and play in the street like the other kids. There was also the constant, looming threat that he would likely die young.

Despite his isolation, he was aware of the outside world, watched TV, and fell in love with Star Wars. He even got to see a special screening of Return of the Jedi in 1983 (in his plastic bubble, of course). But according to an April 1997 article in Houston Press (Bursting the Bubble), he was often very frustrated.

“According to a person David called his best friend, the boy wasn’t struggling cheerfully. In 1978, although he was not quite eight years old, David had realized his life would be lonely, dull, and short. His helplessness enraged him. Before he was born, his body had been donated to science.”

TV news items often made out he was doing his best and having fun. But he’d asked his psychologist Mary Ada Murphy:

“Why am I so angry all the time?”

This did lead to the debate over the ethical decision of his parents. Doctors told them their next child had a 50/50 chance of having the condition, which they decided was worth the risk.

Their son’s lifetime care costs reached $1.3 million, which would be around $5 million in 2025.

His parents blocked their son’s psychologist releasing a book about the case in 1995. Mary Ada Murphy later had the work published in 2019: Bursting the Bubble: The Tortured Life and Untimely Death of David Vetter.

It’s clear from that title what some people still think of the case.

However, the reason David Vetter’s parents went ahead was with a sense of hope—there was a chance with a bone marrow transplant to help their son lead a more normal life. That was their goal. He did receive a transplant from his healthy sister, but this led to an infection and he died several months after the operation on February 22nd 1984.