Celebrating its 50th anniversary is Francis Ford Coppola’s mystery thriller The Conversation. We’ve been meaning to watch this since 2010 and, finally, caught up with it. Oopsie on the delay.

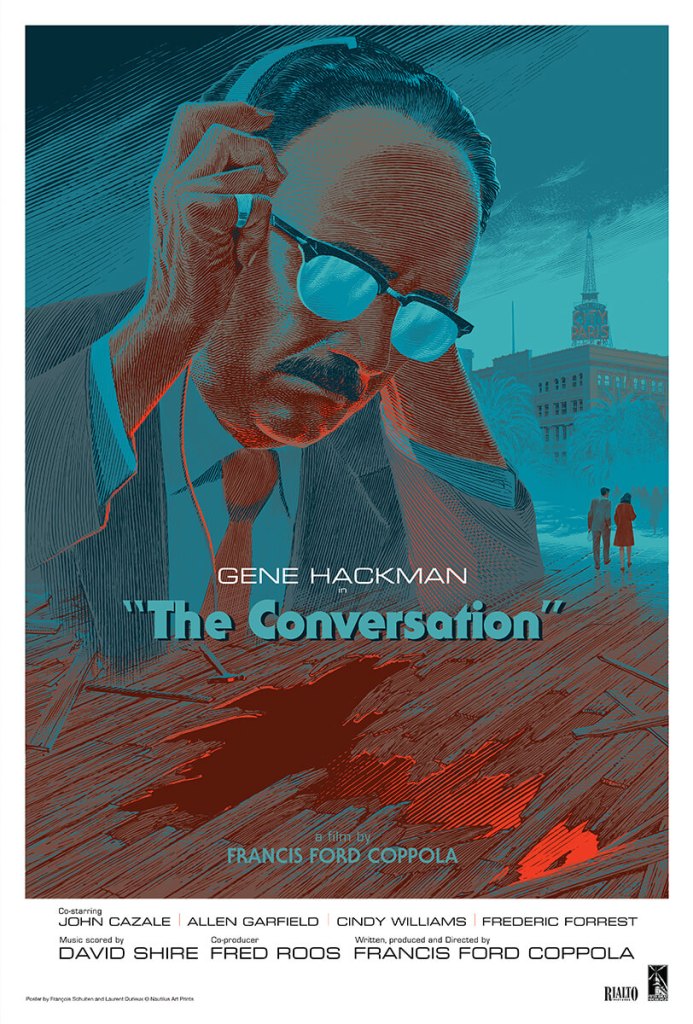

The film enjoyed a full cinematic re-release earlier this year to mark the occasion. As this was an ahead of its time production, starring Gene Hackman, Harrison Ford in an early role, and the legendary John Cazale. It’s impressive stuff and still packs an important message.

Paranoia and Privacy in The Conversation

For a long while now, The Conversation has held this status as a go-to must for film buffs. Its reputation remains as one of the seminal ’70s films, in a decade of often exceptional cinema.

This came two years after The Godfather, so Francis Ford Coppola had already launched his name. The sequel to that came out in 1974, too, as with this film. Coppola was able to do two films in a year as much of The Conversation was shot in late 1972 and early 1973.

The main character here is Harry R. Caul, played by Gene Hackman. It’s this film, William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971), and The Poseidon Adventure (1972) that launched Hackman towards Hollywood royalty status. And he’s bloody great in this subtle, complicated performance.

Caul is an austere Catholic surveillance specialist who takes his faith, and work, very seriously. He’s also deeply private, enjoying solitude, privacy, and playing saxophone (seemingly to alleviate his pent up stress).

He works with Stanley “Stan” Ross (John Cazale).

Cazale only ever starred in five films, all of them being nominated for Oscars. His last role was Deer Hunter, during the filming of which he was severely ill with lung cancer. He’d just married Meryl Streep and died before the launch of the film. This was a a more subdued role for him after The Godfather, but he put on a blinding show in Dog Day Afternoon (1975).

Now, watching the opening segment in 2024 takes away just how groundbreaking the interweaving segments of this film must have been half a century ago.

We always like watching these older films anyway to see what the world was like a decade before we were born. Then finding out about some of the people involved.

For example, the street mime in this scene is Robert Shields. With his wife Lorene, in the 1970s these two were a famous American mime duo. They divorced in 1986, Lorene unfortunately died in 2010, but Robert is now living in Verde Valley of Arizona and works as an artist.

That intro leads to the actual conversation. And we can’t remember any other film where the opening sequence is so essential to the rest of the film.

This segment, starring Cindy Williams and Frederic Forrest, repeats many times across the film. Caul uses his surveillance and tech skills to work around recording issues to unearth a shocking announcement.

The couple above, Ann and Mark, appear to be discussing a potential upcoming murder—against them.

It’s intriguing to see the technology in The Conversation. Old style 1970s, big plastic button recording devices. At the time cutting-edge, now looking archaic. But despite being big and bulky, there was some fancy stuff going on in 1974. All of which paved the way to where we are now.

Which does, unfortunately, raise the prescient message of the film—the invasive nature of technology in our day-to-day lives and public privacy.

Another great ’70s film called Network (1976) with Peter Finch had a similarly prophetic message.

This is why the 1970s remains such a venerated cinematic era.

Caul becomes increasingly obsessed with the young couple and their fate. But h works freelance for a wealthy business to determine what the couple is doing.

This is where we meet a pre-fame, early 30s Harrison Ford starring as Martin Stett (the obnoxious son of a powerful business owner). However, it’s not a big surprise he went on to be a big film star—those are some serious movie star good looks he’s boasting there.

Ultimately, this all leads to the surprise ending. SPOILER ALERT! It turns out the couple, headed by Cindy, were having an affair behind the wealthy business owner’s back (played by Robert Duvall). In the end, they murder him.

Caul is later warned by Stett to back out of any further investigations or face the consequences.

It’s then revealed the business is now surveilling his small flat. Caul has a paranoid fit and shreds the place apart, before trying to calm himself by playing saxophone.

The Conversation is a classic 1970s film in many respects. It has all those qualities as a total slow burner, character development, and reliance on conversations between various individuals.

All of which builds to a genuinely tense, surprising ending.

Although it shows its age in places, which is natural, it’s nonetheless a highly effective mystery thriller. One we think is very deserving of its status as one of the ultimate cult classics.

The Production of The Conversation

The film wasn’t a hit. In 1974 the likes of Chinatown (a Jack Nicholson star vehicle), Earthquake, Dark Star, The Four Musketeers, a new James Bond film, and the second Godfather stole the show instead. A curious, slow burner of a film like The Conversation, just didn’t capture the public imagination.

Off its $1.6 million budget it made back $4.9 million.

As we mentioned early, principal photography took place between November 1972 and February 1973. However, Coppola had an outline for the script in the mid-1960s. This delay between getting the film done is common in Hollywood, with many screenplays floating around waiting to be greenlit.

The film also remains Coppola’s favourite from his impressive canon.

He also later notated the unintentional resonance of the film, which happened to coincide with the Watergate scandal with then President Richard Nixon.

Famously, he resigned from office on 9th August, 1974. The Conversation had launched in April. Coppola was also amazed to find the technology displayed in the film was used to bug Nixon. Neat, eh?

Gene Hackman also rates it as his favourite film he appeared in, for which he specifically learnt to play the saxophone. He was in his early 40s at the time and did himself up to look a bit pathetic. Including with a dodgy moustache and poor dress sense, all to make him look older and a bit fuddy-duddyish.

And that’s a big part of the film, Caul’s boring existence is overhauled by the revelations his day job reveal. But not in a way that enhances his life.

Despite the film’s lack of commercial success, the ambitious themes of the film were rewarded critically. It was nominated for three Oscars (didn’t win any), but won the prestigious Grand Prix du Festival International du Film at the 1974 Cannes Film Festival.

50 years on and its status as a cult classic every film buff should see is firmly cemented into cinematic lore. Our recommendation is to give it a watch.

It sticks with you and will have you checking your home to see if it’s bugged. Which, if you’re a conspiracy theory nut, will have you shredding your home apart. Good luck with that.