Snakes and ladders is one of those rites of passage board games you play as a kid. For BRITISH people that we are, this one arrived in the UK in the 1890s. However, it was created during ancient Indian times.

There’s a giant square ting with gridded sides with ladders and snakes depicted over it. Progress is based on chance as the player (usually a young child) rolls a dice, hoping to land on a ladder and scale to the very peak.

In the active imagination of a kid it’s all very enthralling, so let’s revisit this one and unearth some memories you have locked away of glorious victories and appalling losses.

Understanding the Instant Appeal of Snakes and Ladders

Growing up in the late 1980s and early 1990s, this one was a fairly constant game in school and at home. Just a quick time filler and a bit of a fast-paced rush, with a game over in about 10-20 minutes.

You place the board on the floor and begin, rolling the dice to advance along the squares. The drama begins as follows:

- Landing on a ladder: Up! Up! Up! Glorious victory, winner!

- Landing on a snake: You go back down, you SAD and PATHETIC loser!

So, yeah, you want to be landing on the ladder bits and that speeds you up the board. It’s all down to luck, though, as the old dice is what determines your fate here.

Simple stuff, but brilliant in its execution. It’s instantly appealing for a child no matter where they’re from, which is why it’s remained a classic across the centuries. You play and within minutes can be getting a little adrenaline rush, scaling up ladders, sliding down snakes, and rolling dice. Fun!

The Ancient History of Snakes and Ladders

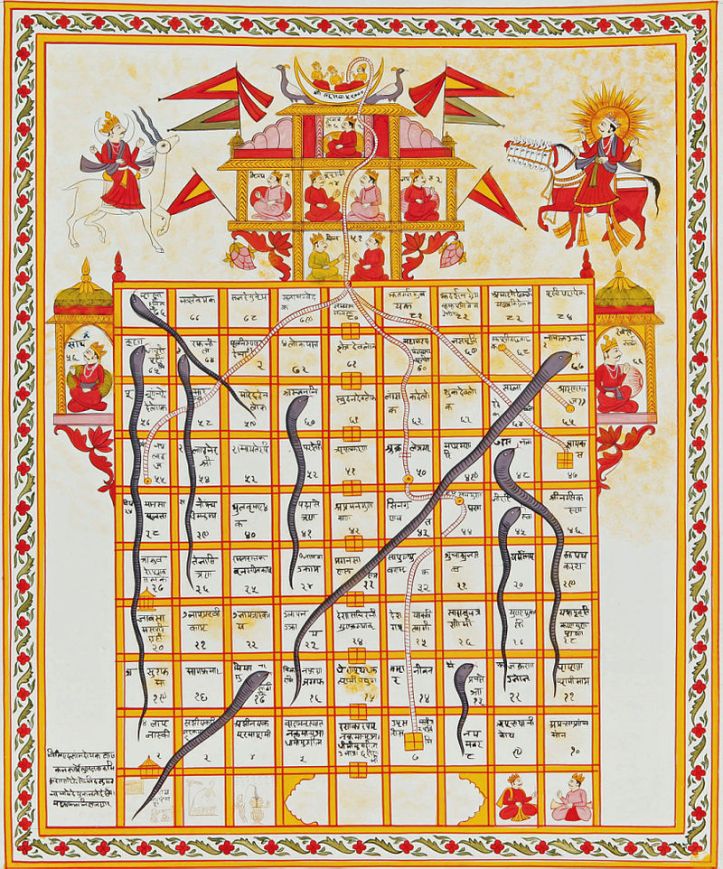

Modern takes on this classic have bright colours and a kiddy appeal. The traditional Indian approach was much more artistic, as with the above 19th century opaque watercolour take.

There culture has the board game based on Jainism, the non-theistic religion of spiritual concepts, non-violence towards animals, and a focus on solitude.

Records of who invented it don’t exist, but it may have been as early as the 2nd century AD. In ancient India the game was called Moksha Patam. Then from around the 10th century it became a part of Gyan Chauper (ज्ञान चौपड़—Game of Knowledge), a series of dice games popular with ancient Indian families. In amongst them was Snakes and Ladders and what’s now called Ludo in the West.

For Indians, it was more a game of morality. More complicated than modern Western versions, it was designed to represent a spiritual journey to the top of the ladder.

Snakes and Ladders was registered as the name in 1892 by the board game manufacturer FH Ayres. They were considered the Rolls Royce of the board game world back then. It may have been the Victorian era, but kids in wealthier families (not the ones sent up chimneys) got to enjoy this title in England for the very first time.

After a few decades the idea became minimalistic. After WWII, the version we know (and perhaps love) was scaled back and became more of a throwaway time filler. But one that’s created many a happy memory all the same.

Back to Square One? Markov Chains and Other Phrases

Did you know the phrase “BACK TO SQUARE ONE” came about due to this title? Worth remembering that and using it constantly going forward (and annoying everyone with your knowledge of this).

Asides from that, the mathematics of Snakes and Ladders is intriguing.

In maff (maths), there’s this thing called an absorbing Markov chain. This is a type of Markov chain in which every chain is capable of being absorbed (that then can’t be unabsorbed once it is absorbed). And a Markov chain is a sequence of possible events where the probability of each event depends only on the state attained previously. Understand? Good, it’s easy.

There’s a thesis on this called How Long is a Game of Snakes and Ladders (1993) by S. C. Althoen, L. King, and K. Schilling. It does depend on the number of squares on the board being used, as each version has a differing number. If it has 100 squares, then it should take about 47.76 moves. And the player who starts first has a 50.9% probability of winning.

This is explored further by Leon Matthews on his site Lost. In his piece Can Snakes & Ladders Last Forever? he reports his findings thus:

“Play for long enough and patterns emerge. Half of all games end after the median of 33 turns. There are two paths to the shortest possible game of 7 turns. If you play a million games, at least one of them will probably take more than 400 turns to finish. The longest game I’ve ever seen took 729 turns to finish.”

And in explaining Markov chains he notes:

“The game board is really a discrete-time Markov chain with 100 states (or 81 if you’re feeling particularly pedantic). I try and avoid terminology when trying to explain (or understand) a new concept. Richard Feynman said something like, ‘If you can’t explain something in simple terms, you don’t understand it.’ Markov chain gets to be an exception only because it has the coolest name. It’s not nearly as complicated (or impressive) as the name suggests.”

Matthews also noted the shortest game he experienced was just seven dice rolls. As a kid playing, you’d probably feel a little short-changed by that. But of the longest game he states:

“Of all the trillion games, the longest took 729 rolls to finish. The second-longest took 666. 33 billion (3.3%) of solo games took longer than 100 moves. Yikes!”

Based on this, he recommends ending a game the moment there’s a winner. Otherwise, if you continue playing the game with kids to determine second and third places, you may well be there for infinity.