After round one of our repurposed old book reviews, we’re ready for round two!

As a recap, when we started doing book reviews on this blog in late 2014. And those early ones, looking back now, were a bit rubbish. And so we’ve been updating them (repurposing old content, as the lingo goes).

Some More Old Book Reviews Made All Shiny and New

We’ve been rather busy, we’ll have you know, as we’ve updated over 30 of these old posts! Here’s another batch of our favourite updates.

These are the books!

And here’s a brief overview of what each one is all about.

Death and the Penguin

“The once terrible was now commonplace, meaning that people accepted it as the norm and went on living, instead of getting needlessly agitated.”

Kicking off the list with Andrey Kurkov’s cult classic Death and the Penguin (1996). It’s an unusual story about a newspaper obituary writer, his pet penguin, and the political battle he unwittingly finds himself wrapped up in

There’s something about Kurkov’s debut novel (in Russian it’s Смерть постороннего—Smert’ postoronnego) that captures the sense of Soviet era collapse and a not too certain future. All done with a sense of dark humour. It’s a great read!

Kurkov is now a major modern Ukrainian writing talent who’s also now a vocal commentator on the awful war in his country

On the Road

“Nothing behind me, everything ahead of me, as is ever so on the road.”

Now it’s time for Jack Kerouac’s legendary On the Road (1957), written in a frenzy of activity over three weeks.

An instant bestseller, the stream of consciousness style of beat generation writing flows like an unrestrained jazz drum solo. And the work is heavily soaked in Kerouac’s era.

Written in the late 1940s, it celebrates a post-WWII sense of personal liberation and youthful hedonism. Kerouac’s alter-ego Sal Paradise drifts across America hitchhiking, sleeping rough, drinking, and partying.

It’s a glorious ode to being young and carefree.

The Book of Disquiet

“Only one thing surprises me more than the stupidity with which most men live their lives and that is the intelligence inherent in that stupidity.”

This was published posthumously in 1982. Fernando Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet is a selection of fragmentary moments jumbled together in no real order.

Pessoa was a writer in his spare time, but never made any effort to get most of his work published, instead preferring to just drift through life as a relative unknown.

These highly intelligent musings on life and everything make for a fascinating look into a life lived in obscurity.

After he died, 25,000 pages worth of handwritten notes were found in a chest in Pessoa’s home. 50 years after that, these were assembled together and published as this book. Essentially, it’s his life’s work right here.

The Call of the Wild

“He was mastered by the sheer surging of life, the tidal wave of being, the perfect joy of each separate muscle, joint, and sinew in that it was everything that was not death, that it was aglow and rampant, expressing itself in movement, flying exultantly under the stars.”

An iconic short adventure book, Jack London’s The Call of the Wild (1903) is brimming with a sense of primal adventure.

Although a short novella, it’s classic adventure writing at its best. Readers follow the life of Buck the St. Bernard–Scotch Shepherd dog. Severely mistreated by various owners during the 1890s Klondike Gold Rush, he eventually finds himself drifting towards his real instincts.

Classic fiction at its best. And as it’s such a short novella, there’s no excuse not to read it.

Cancer Ward

“It is not our level of prosperity that makes for happiness but the kinship of heart to heart and the way we look at the world. Both attitudes lie within our power, so that a man is happy so long as he chooses to be happy, and no one can stop him.”

From the Russian literary genius Alexandr Solzhenitsyn’s Cancer Ward (1966) remains a searing piece of social commentary on the state of mid-20th century Russia.

The narrative begins in 1955, shortly after the death of Joseph Stalin. And now a group of cancer patients, stuck on a primitive hospital ward, contemplate their role in a former dictator’s Great Purge.

Although a quite bleak novel, it’s also stunningly gripping. This is a big read, but one that’s essential for any serious book enthusiast.

Miracle in the Andes

“I would teach myself to live in constant uncertainty, moment by moment, step by step. I would live as if I were dead already. With nothing to lose, nothing could surprise me, nothing could stop me from fighting; my fears would not block me from following my instincts, and no risk would be too great.”

Arguably the definitive account of the 1972 Andes Plane crash, survivor Nando Parrado’s Miracle in the Andes (2006) is at once harrowing but deeply humanistic.

You can read this incredible story in many ways. How to deal with seemingly impossible adversity. Coping with grief. Finding a reason to live. It’s all in here.

Parrado’s work is very humble and moving, not least as he lost his mother and sister in the disaster. Yet despite that terrible loss, he promotes love as the answer.

Factotum

“Frankly, I was horrified by life, at what a man had to do simply in order to eat, sleep, and keep himself clothed. So I stayed in bed and drank. When you drank the world was still out there, but for the moment it didn’t have you by the throat.”

Another one of Bukowski’s very drunken accounts of lowlife leering, Factotum (1975) is very funny, very sad, and very ridiculous.

Once again readers catch up with his alter-ego Henry Chinaski. He’s sticking it to the man, drifting like an idiot from one terrible, mundane job to the next. As he does so… he drinks a lot!

The joy of the book comes from many elements of schadenfreude delight as you revel in Chinaski’s bumbling antics. But Bukowski’s sardonic sense of humour also sprinkles the work with a boozy charm.

Ham on Rye

“The problem was you had to keep choosing between one evil or another, and no matter what you chose, they sliced a little more off you, until there was nothing left. At the age of 25 most people were finished. A whole goddamned nation of assholes driving automobiles, eating, having babies, doing everything in the worst way possible, like voting for the presidential candidate who reminded them most of themselves.”

First published in 1982, Ham on Rye was Bukowski’s most normal book! Doing away with the more leering behaviour of his alter-ego Henry Chinaski, it’s candid and the writer’s most autobiographical work.

And it’s a very sad read. His difficult upbringing is explained, with a father who beat him. Then his terrible acne (alongside average looks) ostracised him from his peers.

Those formative years set in place many defence mechanisms for Bukowski’s often caustic personality traits. But the dry humour remains throughout this book, too, and we do think it’s his best piece of writing.

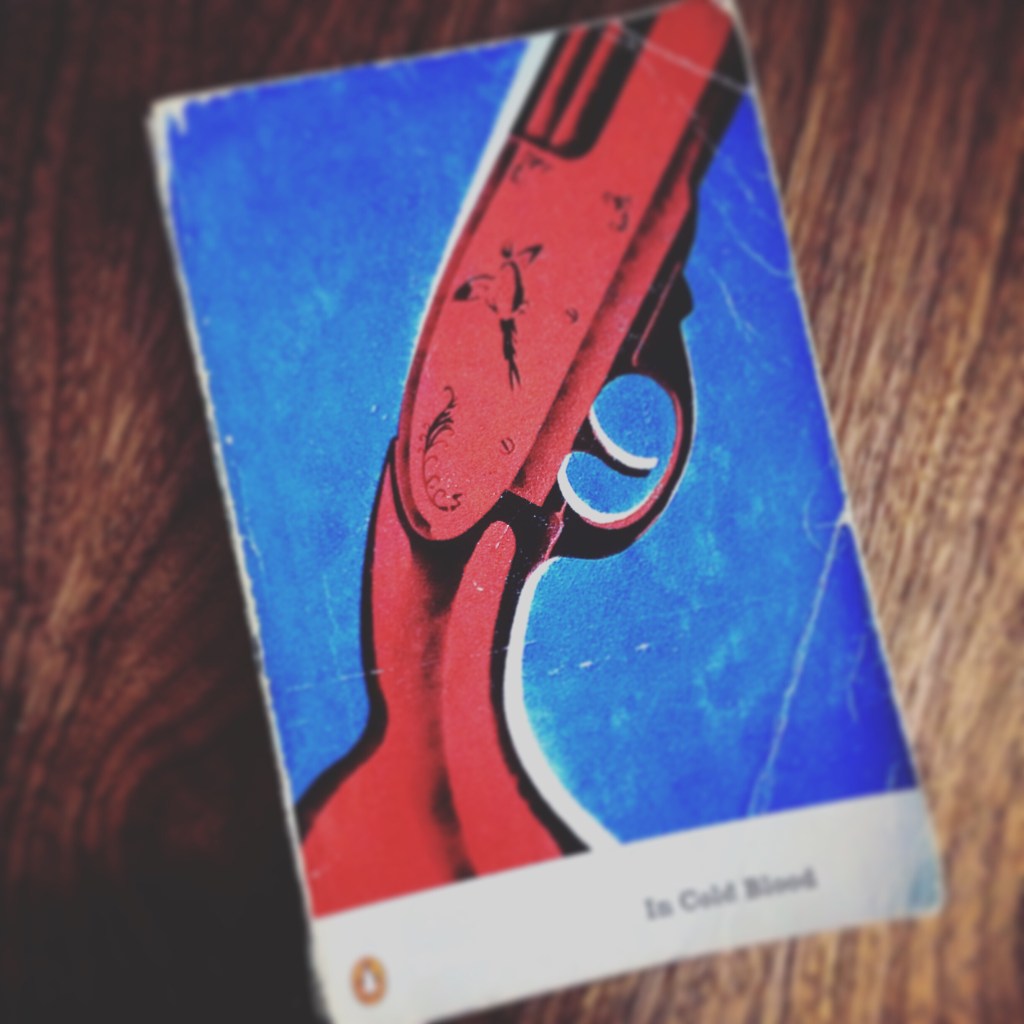

In Cold Blood

“There is considerable hypocrisy in conventionalism. Any thinking person is aware of this paradox; but in dealing with conventional people it is advantageous to treat them as though they were not hypocrites. It isn’t a question of faithfulness to your own concepts; it is a matter of compromise so that you can remain an individual without the constant threat of conventional pressures.”

Truman Capote’s masterpiece, In Cold Blood (1966) is classic work of crime non-fiction. Detailing a horrendous crime from the 1950s, Capote set out on an investigative journalism odyssey.

The process of writing the book book many years, psychologically left him exhausted, but it did result in one of the 20th century’s great books.

However, he never wrote another full novel again. But… for a while, he was America’s most famous writer. That was all down to In Cold Blood.

Game Over

“The kanji characters he chose to make up the name of his new company—nin-ten-do—could be understood as ‘Leave luck to heaven,’ or ‘Deep in the mind we have to do whatever we have to do.’”

One of the greatest books about video games ever written, David Sheff’s Game Over (1993) documents Nintendo’s startling rise to international business prominence during the 1980s.

It’s all in here. The opening of its American branch and the bizarre, triumphant victory in a Donkey Kong copyright lawsuit. The battle for the Tetris rights. Obliterating the opposition with the Nintendo Entertainment System.

Nintendo’s actions in the Eighties set the foundations for modern gaming. So, this makes the work a fascinating insight into a lot of pioneering business, and creative, mindsets.