Hailing back to 1943, abstract expressionism was a direct response from American artists to the chaos of World War II. By the 1950s, it had mainstream popularity and from it emerged the likes of Barnett Newman, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Barbara Hepworth.

Decades earlier, abstract pioneers such as Wassily Kandinsky laid the foundations for this movement, alongside the previously forgotten genius of Hilma af Klint.

But abstract expressionism certainly is divisive. For some people, you may look at a piece and see a mishmash of squiggles. Anyone can do that, kind of thing. Whereas we, with our autistic brains, see something rather magnificent.

Thus, as we immerse ourselves further in the world of art, we picked up David Anfam’s Abstract Expressionism: Second Edition (1990) to dive deeper into the swirling angles and shapes.

Abstract Expressionism and, No, Your Cat Couldn’t Make That

Given the devastation of WWII, it’s not surprising some artists couldn’t find it in themselves to paint “normal” stuff.

With so much carnage unleashed from Hitler’s far-right regime, creatives perhaps rightfully weren’t going to paint some lovely daffodils in response. It would be improper, almost insulting to the victims of war. Barnet Newman (1905-1970) said this.

“We felt the moral crisis of a world in shambles, a world destroyed by a great depression and a fierce World War, and it was impossible at that time to paint the kind of paintings that we were doing—flowers, reclining nudes, and people playing the cello.”

This is all an essential aspect of understanding abstract expressionism.

The non-figurative mass of lines, shapes, and colours may appear simplistic. But we’re talking about deep felt, emotive, philosophical, psychologically charged creative responses to an unprecedented situation.

Out of it came stuff like Newman’s series The Stations of the Cross (created between 1958 and 1966).

That’s a classic bit of abstract expressionism. The themes of exploring the unconscious, fuelled further by surrealism and the works of psychologist Carl Jung (synchronicity and all that jazz).

Existentialism is a clear influence, too, from the likes of Jean-Paul Sartre (see Being and Nothingness). Some people find all that sort of stuff bleak and depressing, but we view it more as the reality of existence. Barnett and the work of his peers may seem meaningless, but it’s a combination of nothing and everything.

In amongst the abstract is inherent absurdity.

That does have meaning for many people. As we covered on our Mark Rothko feature, some people looked at his paintings and burst into tears. Why? Well, it’s all a deep and meaningful personal experience.

Beyond the Squiggles—Understanding Abstract Expression

Anfam’s work covers eight chapters, during which his writing style is kind of overly sophisticated. The first edition was published in 1990 so maybe it was a thing of its time, but the pontificating does get a bit pompous at times.

Really, we’re not sure what he’s banging on about a lot of the time (we favour Orwell’s writing lesson of writing in clear English instead of trying to sound big and clever). But Anfam sure knew his bloody stuff, even if he is rather humourless across this work.

Especially considering he’s covering some anarchic characters. The pre-punk artists such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko—unruly, drunk, and unhealthy. They died due to hedonism and mental health issues. Anfam notes this.

“Consciousness as a leitmotif evolved from the acute self-awareness of the artists themselves. Time, identity and their relationship to the world were fundamentals.”

Anfam details the troubles many of the artists had in their formative years. Rothko subject to antisemitism, Gorky and de Kooning immigrants, Pollock’s severe insecurities etc. All heighted by WWII and other personal, or wider, tragedies. And that for us is what this is all about—a different take on the human condition. Taking Sartre and Jung’s philosophising and putting it into creative motion.

Adolph Gottlieb (1903-1974) represented the triumph and tragedy of life through his abstract art. Below is Cadmium Red Above Black (1959). In 1970 he was left paralysed, except for his right arm and hand. What did he do? He kept painting.

Not that it was all doom and gloom. Helen Frankenthaler (1928-2011) offered work that was colourful and upbeat. On the whole, though, we’re talking about weighty topics. Such as with Willem de Kooning’s Excavation (1950).

From 1950, de Kooning turned his attention to women as his subject matter. That moved away from often formless works for his peers, instead offering the feminine form in some rather unusual sculptures and action paintings.

This wasn’t some sexist thing, either, it was intended as promoting the active feminist movement in the aftermath of WWII.

But for now, we must take a detour to the most obvious name of them all. The action painter maestro himself.

Jackson Pollock’s Tangled Legacy

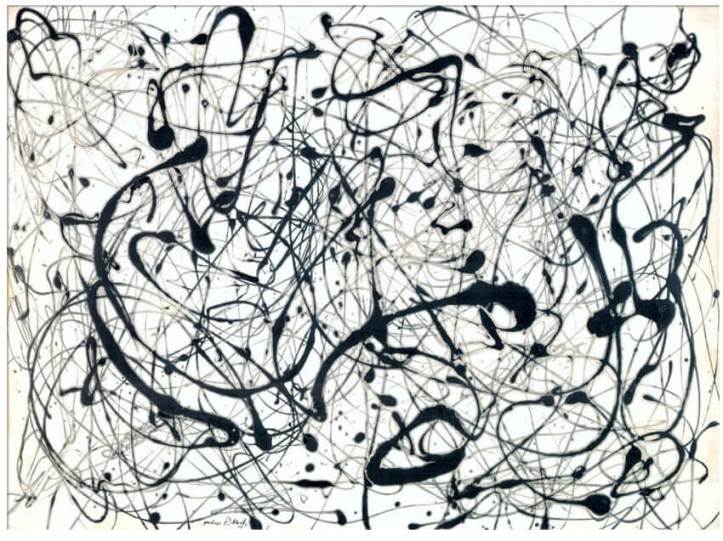

Jackson Pollock is, arguably, the most famous of abstract expressionist. His weirdly wonderful, tangled mess paintings with that distinctive drip style sploshing of paint? Very influential.

Branded by the art community as “Jack the Dripper”, he’s very divisive—many consider his work overrated and that he was just a bit of a drunken prat, dripping his way to unfounded glory. A cat could have done that.

We nod to the always brilliant Nerdwriter for some notes on that.

Pollock seems to represent everything people love or hate about abstract creativity. But there’s no denying he changed modern art and his legacy still burns bright.

As fans of his work, we do like to champion it over suggesting he just dripped paint everywhere. Rather, we wonder what was going through his mind when he did this thing (Eyes in the Heat—1946).

Or this (No. 14 Gray—1946).

Pollock’s influence deeply affected one young Manchester artist and musician, who went on to found groundbreaking band The Stone Roses. John Squire eventually co-wrote the song Made of Stone, which seems to nod to Pollock’s death in a car crash in 1956 (he was under the influence).

Back in the late 1980s, Squire’s artwork for the band was all Pollock inspired. It adorned all the singles and iconic debut album cover.

He’s since semi-retired from music, but not from art. And he’s a very talented painter in his on right. Take a look at his work: John Squire art. Naturally, he’s quite heavily embedded in abstract art, take a look at his encaustic paintings.

Considerations on the Cultural and Political Influences of Abstract Expressionism (innit)

That’s what it’s all about. The nature of this book is the impact of the art on the world, with a significant focus on Pollock, told in a very rambling, dry, continuously aloof TOV. About as stereotypically studious as you can get.

But… we like the book. Anfam’s expertise is clear and he provides a thorough history. We do wish he’d lightened the tone a tad, maybe cracked the odd joke (Jackson Pillock etc.), but for a sweeping introduction to abstract expressionism it’s a fabulous start. And a wonderful insight into the talent of the era.

The movement isn’t dead. Plenty of artists across the world still back its cause.

Perhaps it’s because we’re autistic, but this sort of thing greatly appeals. Maybe as it makes up the jumbled mess of our brains, trying to balance out communication issues with disrupted sensory experiences and the like.

It can be very confusing and took a long time to master.

These paintings often have no clear meaning, are strange, odd, and are outsiders of conventional art. For us, they offer some sort of strange reassurance. As if they’re talking to us, in the know we’re a wee bit abstract and unconventional, too.