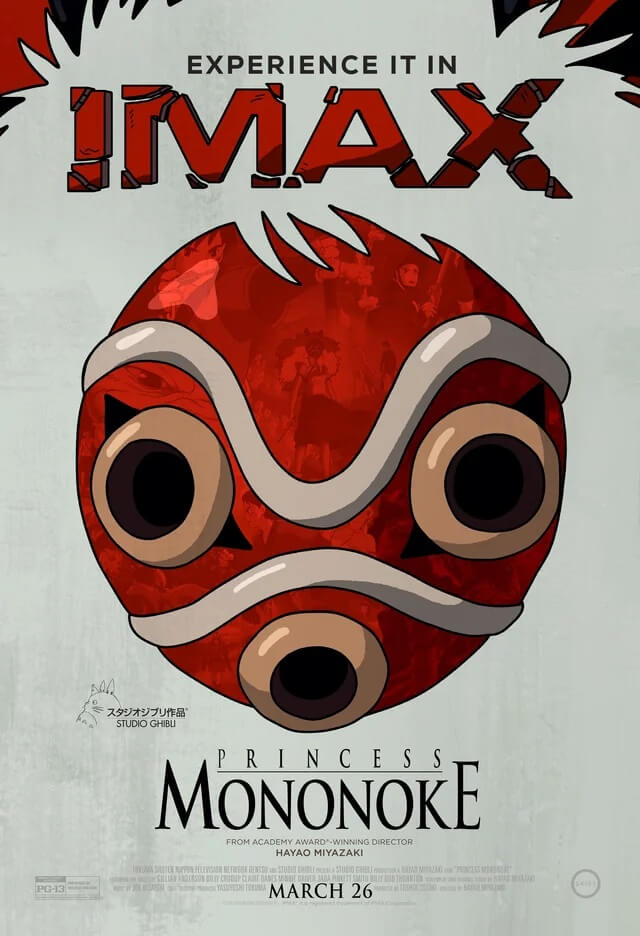

With Princess Mononoke (1997) getting a surprise re-release at cinemas here in the UK, all in glorious IMAX, it’s been a happy few days.

Some films demand to be seen on the biggest screen, so getting to see Studio Ghibli’s masterpiece in Manchester was a real privilege. With its complex themes, this is a challenging movie. One with incredible relevant to modern life and warring factions—a film that sees with eyes unclouded by hate.

IMAX and Princess Mononoke as the Perfect Cinematic Match

We’d argue the cyclical nature of societal violence and war are the central themes of Princess Mononoke.

Director Hayao Miyazaki launched the film in 1997 at a time of relative peace in the world, but its 2025 re-release aligns with notable, horrible political turmoil. It also marks 80 years since WWII ended.

The film covers advanced territory, with mortally wounded protagonist Ashitaka looking on aghast as all around him lose their mind to hate, revenge, and vengeance.

We meet forest spirits, various animal factions, and humans having turned on each other and ready to plunge into war. Anger and frustration overwhelms everyone. Ashitaka decides to rectify the situation—his life ever-dwindling due to that demonic curse.

Miyazaki has featured strong female characters throughout his career. He’s said:

“I create women characters by watching the female staff at my studio. Half the staff are women.”

This makes the director’s canon authentic are free from tedious cliches or sexualisation. There’s the feral San (サン) and domineering Lady Eboshi (Eboshi Gozen—エボシ御前) who dominate the narrative. The former is the princess in question for the plot.

Lady Eboshi and San despise each other, with Eboshi the film’s main antagonist. But she does come to realise the error of her ways and choose a more righteous future.

Ashitaka and San also only form a close bond, with the latter choosing to remain with the wolf clan she was raised with. There are no predictable romance cliches here. Again, adding to the compelling narrative and its unique arc.

All this plays out to the backdrop of spectacular natural scenery, as we covered in our recent Journey to the West landscape feature.

Miyazaki had the ideas for this film down as early as 1980. Everything was loosely based on the fairy tale Beauty and the Beast (1740) by Gabrielle-Suzanne Barbot de Villeneuve.

For this film, the Beast element is realised as a spirit—Mononoke (物の怪).

These populate Japanese classical literature and folklore (dating to the Heian period of 794-1185). The term isn’t welcoming, suggesting Lady Eboshi’s industrial station and town invented the term to demonise San.

It’s still a fantastic film. It had been a fair while since we’d watched it all the way through, but the message is clear and prescient. It’s like a message to future generations—don’t let anger overwhelm you. The film’s characters are lost in the depths of tribalistic defence and all the while Lady Eboshi’s capitalistic venture stirs them up further.

In Ashitaka, Miyazaki created a brilliant and noble character. He’s always sure of his mission and never waivers, lending a fairy tale edge to proceedings—do we have any political figures in modern times to guide us through our troubles?

Yes. It’s just they’ll likely be drowned out by more hate-filled agendas.

Regardless, Princess Mononoke is a film of hope and dealing with destructive aftermaths. We can all learn a great deal from it.

Princess Mononoke’s Score

Composer Joe Hisaishi completed the score, a long-term collaborator with Studio Ghibli. Basically, the John Williams and Steven Spielberg partnership of the East.

We once saw a journalist criticise the soundtrack as poor… it really made no sense as this is fantastic stuff from start to finish. It really adds a great deal of dramatic clout to the plot, help lifting any of those tedious ideas animated films are “for kids”.

There also more playful elements, such as the lively and mischievous section for the Kodama forest spirits.

This is one of the more uplifting parts of the plot, nodding to the sense of divine spirituality and natural world that dominate much of the film.

It’s a fine piece of work with a heavy emphasis on brass instruments, with several looping melodies throughout to focus on the epic scale of the adventure.

Whew, so long I missed my lunch! This movie sounds like a delight.

LikeLiked by 1 person

One of my all time favourites. Yeah, if you haven’t seen it watch it pronto. 🐺

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m on it!!🐹

LikeLiked by 1 person